This post contains affiliate links, which if you click and purchase the project, give me a small kickback.

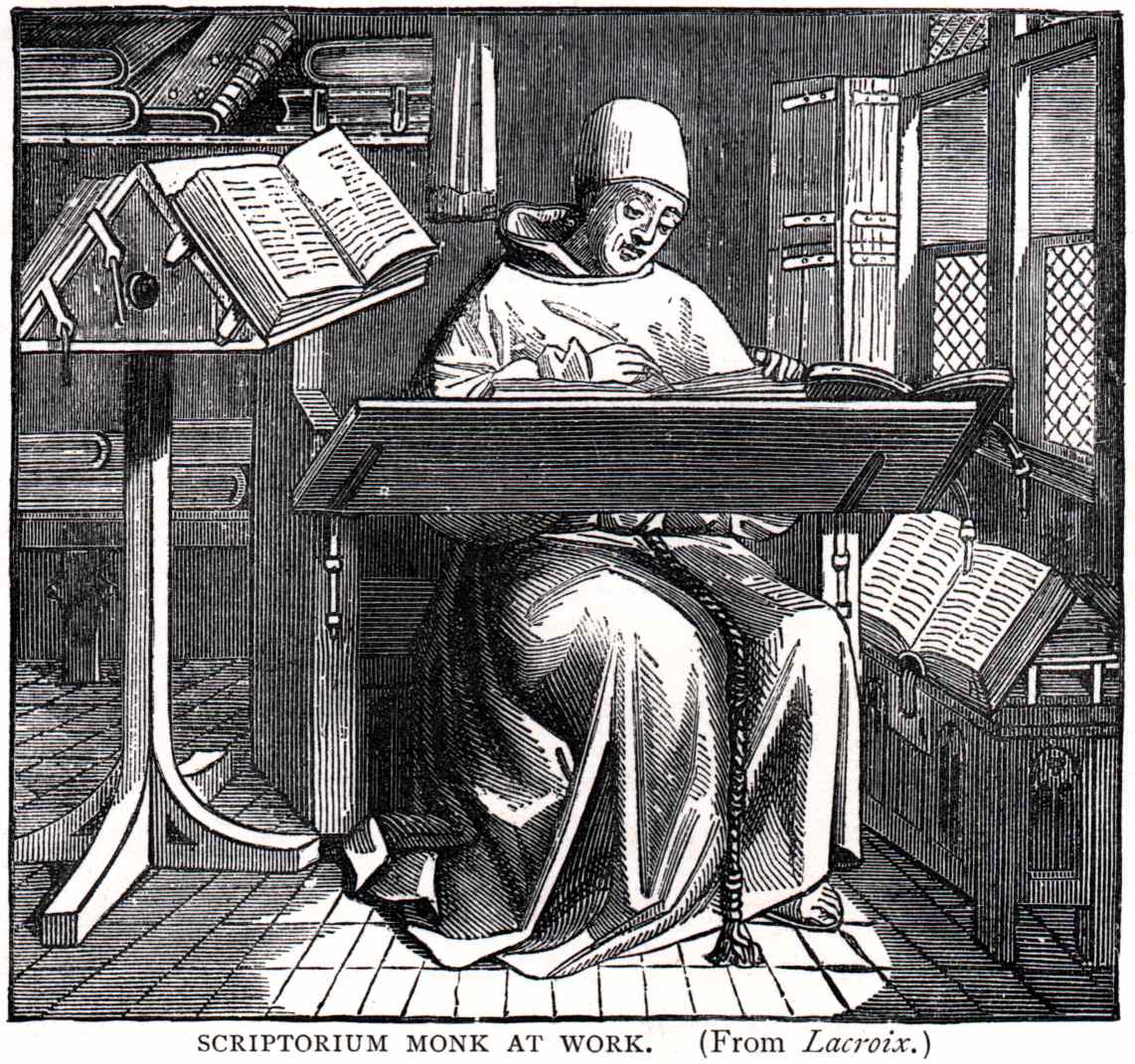

It can be very tempting to establish all sorts of details about a world, creating a virtual encyclopedia, or a set of linked wikipedias, meandering about and naming heritages and establishing bloodlines and considering traditions in towns that go back hundreds of years; this sort of “gritty” worldbuilding has come into vogue, and there are a variety of tools that will help and encourage you to do it (Scrivener, and world anvil spring to mind). Choosing to do this kind of excessive worldbuilding, and trying to establish a world that fits together seamlessly and feels lived in can be a wonderful experience and tremendously rewarding. However, if you choose not to omit details such as birth dates and horse’s sires, the exact town that cotton is produced in and the exact British Thermal units of a fireball spell, your readers will start to pick apart your work.

That kind of detail invites fans who obsess over details, and they will start to look for (and find) the inconsistencies. In “The Gone-Away World” by Nick Harkaway (an excellent book) there is a pipeline that goes all the way around the world. That doesn’t really make any sense, there’s nowhere (except the poles) where you can go all the way around the world on land. It simply isn’t concerned with that kind of worldbuilding and therefore doesn’t invite scrutiny of that nature. I think (and hope) that if you confronted Harkaway with this inconsistency he’d laugh politely and give a shrug or act awkwardly because you’re acting awkwardly; because that isn’t the point of the story.

If the point of your story is actually to reveal all the carefully orchestrated details that you’ve come up with in epic worldbuilding sessions, then it isn’t really a story at all, it’s an encyclopedia or a role-playing game supplement. There’s nothing wrong with these things, and in fact, these sort of things have occasionally been worked into really excellent books such as Dictionary of the Khazars, writing fictional non-fiction can be excellently and truly rewarding, and also invites speculation, and reader interest. Famous literature such as Don Quixote (and especially it’s sequels) engages in this kind of blurring the lines between reality and fiction, the term kayfabe has been invented to help explain it, particularly in regards to professional wrestling and the concept has spread to things like pop singer feuds.

The trouble is, it’s hard to do well. It’s pretty easy to write a standard adventure type novel that involves a lot of journeying and excessive description using an omniscient narrator. But every detail you add should be there for a reason, to tell part of the story, and ultimately to help you explore themes. If not, it’s probably just bad writing.